The DocuCopy series of microfilm copy machines landed a big client in 3M – and demanded a whole new set of rigorous production controls to meet quality standards.

The DocuCopy series of microfilm copy machines landed a big client in 3M – and demanded a whole new set of rigorous production controls to meet quality standards.

Under the OST and EOM names, Digital Check’s precursors in California worked on a lot of high-tech, high-profile projects. But as the 1980s dawned, analog began giving way to digital, and the types of projects that had once been expensive feats of mechanical engineering quickly became possible to do for a fraction of the cost using microchips and software to control a device. The age of mass-market electronics was arriving.

“It was a huge change here,” chief engineer Phil Barboni recalled. “Our engineers were used to being on the bleeding edge of technology and working on bleeding-edge projects, but that was no longer the right thing to do. We had to make a decision that if we were going to survive as a company, building a small quantity of custom-built, very expensive equipment was not the way to do it – and we would have to worry about things like cost and repeatability.

“Most of the other engineers quit, because that was not what they wanted to do. So a lot of new staff came in, and they had to be hired with a different mindset for commercial products.”

The first of those new products, built under the new company name Data Conversion Inc., or DCI, was 3M’s microfilm scanner. That deal came out of a very exciting, high-pressure sales pitch: DCI’s product group was called in for a meeting with 3M’s executive board for a demonstration of the new device – but the machine didn’t arrive in time. After a seemingly endless delay in which the DCI team had to stall for time, the device finally showed up, and when they put it through the paces, the 3M side was impressed.

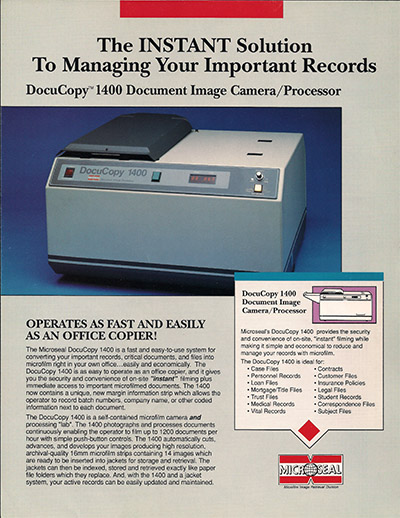

Up until that point, capturing a paper document to microfilm involved a lengthy multi-step process of photographing the document, developing film, then finally repurposing the film to microfilm or fiche format. The DocuCopy acted as a self-contained “lab” that took care of the entire process at once, and output a strip of microfilm directly from the originals in a matter of seconds (at top speed, it could transfer more than 1,000 sheets per hour to microfilm). The live demo impressed the 3M executives so much that their chairman announced his intention to license the DocuCopy on the spot.

At first, Barboni and his team were all smiles – it was by far the biggest production agreement they’d ever signed – but they were also about to get a rapid-fire introduction to the world of big-time manufacturing.

When DCI was first getting started with the contract, there was a lot of enthusiasm – most of the employees thought it was a slam dunk. But soon, 3M’s people started coming out with rules, inspections, and so on. Inspection of parts on arrival; acceptable quality levels; tolerances of measurements on sheet metal; blemishes in the paint – in every case, 3M defined what was acceptable.

Chief engineer Phil Barboni, left, helps inspect the internal components of a nearly-assembled DocuCopy 1400 machine.

Chief engineer Phil Barboni, left, helps inspect the internal components of a nearly-assembled DocuCopy 1400 machine.

Barboni remembered one experience when he had sent samples to 3M, only to have them returned because the screen-printed 3M logo didn’t match their exact shade of red. It was an important message at a crucial turning point in the company’s history:

“When I had looked at it, I couldn’t tell the difference. If you’re going to do work for 3M, you have to have very precise control, discipline in quality control and documentation-wise, do it the 3M way. If it had the 3M name on it, it had to look like they had done it themselves. That’s a very good lesson to learn early on if you want to do business with big companies … When you’re used to doing it, you understand why 3M is what they are. The reputation for quality and reliability is for a reason.”

The 3M-approved process required tracking lots and batches of parts that could then be connected to the finished products by serial number in case of problems out in the field. But while microprocessors were quickly becoming integrated into DCI’s products, office computers were not yet commonplace, so a paper tracking process was standard procedure. Each microfilm copier had a “traveler” – a piece of paper that went along with the machine as it was built, and signed by the assembler (or assemblers) after each step.

Much of what Digital Check does today in terms of quality and inspections can be traced to the 3M project. The same quality control, redundant testing, and tracking the entire process from beginning to end originated with those first contracts in the 1980s.

With the cutting-edge technology that EOM pioneered in the 1970s, the company didn’t do those things – but when you’re producing small quantities, you can get away with it. With the VAMP (EOM’s portion of the military flight simulator), Barboni inspected every unit personally. But with the 3M contract, the company was suddenly building thousands of devices a year. “You couldn’t have one person; you needed a system,” he recalled. “And if you followed the system, you got the results you wanted.”

The microfilm scanners wound up being the highest-volume product that DCI had ever manufactured, with a production run of 15 years, and many of the principles picked up then remain alive in current company culture. Another learning experience came from working with Japanese partners in the early years of the check scanner business.

Parts of DocuCopy machines sit ready for assembly at the DCI plant in Southern California.

Parts of DocuCopy machines sit ready for assembly at the DCI plant in Southern California.

As check scanner volume grew in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company simply ran out of space at its factory, and so decided to outsource some of the manufacturing. It didn’t take too long to zero in on Japan because of its reputation for diligence and quality. Much as 3M had insisted upon years earlier, the partners were told they had to use Digital Check suppliers, get the same parts at the same price, and spent a significant amount of time in Southern California watching how the machines were built. The Japanese partners, according to Barboni, were continually frustrated that they could never match his own costs or quality-control results.

Of course, the flow of knowledge wasn’t all one-way. For instance, the first time the Digital Check team visited the partner’s factory in Japan, they noticed that all the workers were standing up, and the workstations were built high deliberately. The Japanese had done an analysis and found that people were more alert, made fewer mistakes, had fewer aches and pains, and actually preferred standing – so Digital Check introduced the practice into its own factory, giving workers the choice of sitting or standing. Even today, on the CX30 scanner assembly line, you’ll see about half the people standing and half sitting.

Looking back on those lessons decades later, Barboni saw a reflection on the changing attitudes toward manufacturing and foreign imports. “There are inevitably some cultural differences at work – obesity is not a problem in Japan, so weight and body type never even comes into their thinking. But it’s the kind of thing that gets Americans out of their comfort zone. You see something being done differently in a foreign country, and your immediate reaction is ‘I don’t like this; the way it is at home is better.’ Then after 10 years you go, ‘Hmm, maybe it’s not so bad.’ Then after another 10 years you go, ‘Maybe I prefer something here.’ So we didn’t just stumble into these habits – they developed over the course of 25 or 30 years.

“A long time ago, this was the kind of process that you needed to have to become successful. This country is very different today than it was then – you wouldn’t do anything to sacrifice credibility. Today, we often have problems with simple things. Look at manufacturing today, and it’s a totally different mentality: You go in expecting problems in the first place.

“If you want to see how it’s changed over the years, look at Japan, for instance, when they decided they wanted to get into the auto business. When they started out, they had no reputation; they were going up against Ford and General Motors from scratch. But they were smart enough to apply the principles and methodologies to improve – a lot of the same methodologies that we learned in the 3M period, and that the U.S. used to do. An over a period of 10 years, they put Ford and GM to shame. Then Hyundai and Kia are another perfect example – they saw what the Japanese did, and those companies are smart, dedicated and meticulous, and they said, ‘We can do it too.’

“If you didn’t learn this stuff from a customer demanding it of you, I don’t know if you’d learn it. And most of our competitors aren’t even manufacturing in the U.S. at all anymore. I didn’t like hearing it at the time, but I’m glad we did those things.”